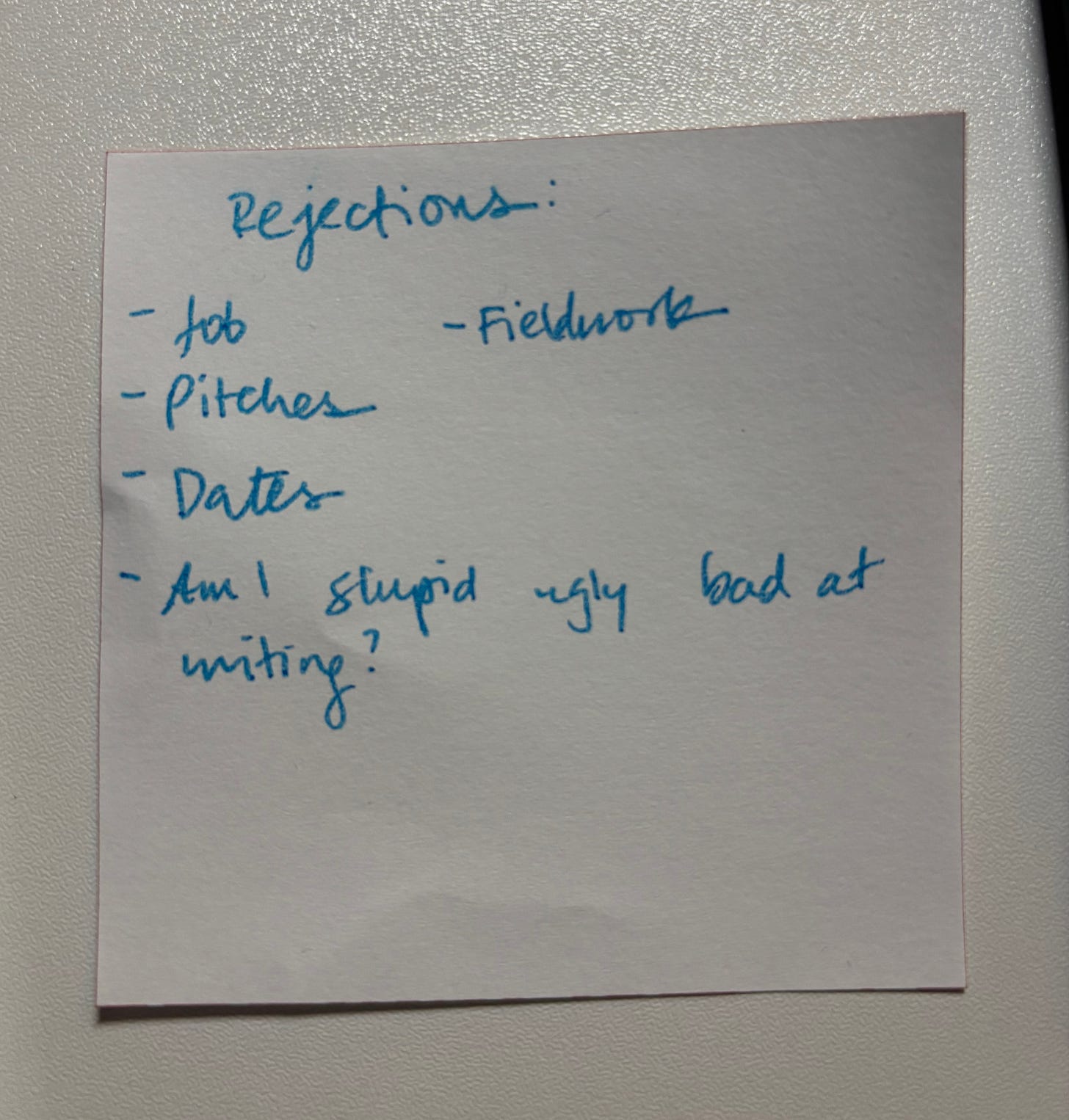

Last Friday in a flash of rage I scribbled the following on a sticky note:

Rejections:

Job

Fieldwork

Pitches

Dates

Am I stupid ugly bad at writing?[sic]

It’s funny to me now that that’s where my mind jumped. Stupid, ugly, bad at writing. Three of the worst things I could be.

Should I elaborate? I’d just gotten word that a publication I hardly respect was passing on a pitch for a piece that I would arguably be the best person on Earth to write. Earlier, I’d heard back from another publication —one I actually respect — that they were passing on a different pitch I was working on (understandable). That was all after I’d gotten rejected from two more postdocs (to add to many other job rejections from the weeks prior). And that was all after multiple different people kindly let me know they didn’t want to go out with me [temporarily/anymore/at all]. And before another person let me know they actually didn’t want “anything romantic” at this time. Awesome. Thank you.

Surely I must be at minimum ugly or off putting, but so much of life is quieting those concerns regardless of their legitimacy. Two things have kept me going: (1)

telling me that a deluge of rejections also means you’ve been ‘putting yourself out there,’ which is something to take pride in; and (2) this video of tennis player Mirra Andreeva after she won the Dubai Tennis Championships.Andreeva is 17, has been for what feels like years. (To quote my friend Maame, “I’m over her being so young, the rest of us are grown.”) You wouldn’t be able to tell her youth from the clip; she comes across as unassuming, stoic, wise. Andreeva has the intensity of a professional tennis player and the gravitas of a tenured monarch. Yet she’s hardly on top of the world — In fact, she only recently cracked the top 10.

Tennis1 is notorious for having a particularly challenging mental game. It is maybe self-evident in the post-Challengers era that tennis involves a very intimate form of warfare in a way most other sports don’t. You get under each others’ skin, you beg for reprieve, you ignore each other and lure each other in. You collaboratively find rhythm, then break it. Push/pull/give/take. You suspend the other person’s humanity — and your own — to turn them into something more animalistic. They’re a predator. They’re…prey? Partner? As Zendaya’s character Tashi Duncan remarks in Challengers, “It’s a relationship.”

Patrick: Is that what you and Anna Mueller had today?

Tashi: It is, actually. For about fifteen seconds there, we were actually playing tennis. And we understood each other completely. So did everyone watching. It's like we were in love. Or like we didn't exist. We went somewhere really beautiful together.

Its not surprising that the psychosexual drama of tennis would intrigue the filmmaker Luca Guadagnino, an auteur of lust and longing.2 As the screenwriter Justin Kuritzkes (famously Celine Song’s husband) recalled, Guadagnino had once told him, “I know next to nothing about tennis, but I know a great deal about desire.”

Not only is tennis about relational vulnerability, it’s also about speed. You are on your own, more or less, and yet you have almost no time to process what’s happening to you. At least not in the ways you’re usually taught. Instead, your game happens on the level of instinct. As David Foster Wallace — a decently strong juniors player who wrote a number of essays on the sport — detailed in in his essay on the brilliance and beauty of Roger Federer, “pro tennis involves intervals of time too brief for deliberate action. Temporally, we’re more in the operative range of reflexes, purely physical reactions that bypass conscious thought.” It’s a serve, then shot after shot after shot, until the point is over. While the sport is dynamic, it involves repetitive training to develop a sense of “feel.” You don’t have time to think during a rally, so you have to trust yourself.3

On top of all that, the cruelty of hope is inherent to the game. Unlike most other competitive sports, it’s possible for either player to win a tennis match at any given point. In most other competitions, a clock or a set number of rounds dictates the duration of gameplay. It’s extraordinarily unlikely, though perhaps not entirely impossible, for a team down 0-3 in late second-half stoppage time to still win a soccer match. But tennis has no clock; a match isn’t over until the match is won. Match points can be saved, comebacks can be had — and they are, frequently. (It’s not uncommon to see a tennis commentator tweet something like “[tennis player] won this match.” with a screenshot of a scoreline showing said tennis player on the verge of a loss, often facing multiple match points.)

What does this kind of rebounding require? Is it desire? It’s embarrassing to want things, even more so to try and get them. Yet in tennis, wanting — hunger — is seemingly the whole point, and not trying is far more humiliating than want. You can still win, if only you can just get the next point, and the next point…

I’ve found there are two schools of thought when it comes to athletic ambition. The first, more traditional perspective is best reflected in corny aphorisms. E.g. “If you can believe it, the mind can achieve it,” a phrase that looms over the treadmill in my building’s dinky low-occupancy gym; or, “everyone wants to be a beast until it’s time to do what beasts do,” oft-repeated by my friends and inspiration for the following fake instagram post I made last year to motivate me during marathon training:

These quotes often revolve around themes of overcoming fatigue or frustration — only then do you achieve greatness. Contrast this with the second perspective, the gentle “self care” approach to sport: Just as there are athletes who express that an aggressive urge to win drives them to success, there are a (growing?) number of athletes who describe an almost Buddhist sense of detachment and inner peace as their counterintuitive way to get results.

This inner-zen approach is perhaps best demonstrated in Madison Keys, the underdog winner of the Australian Open title this year. Keys was a prodigious young player who was exalted as one of a handful of American women’s players who could follow up Serena Williams’s dominance. Her AO win is a comeback story — a player plagued by heartbreaking losses and injuries who finally won a slam, years later, at age 29, besting the reigning champ Aryna Sabalenka. Keys explained how letting go of the desire to win a grand slam is what ultimately freed her to win one. “From a pretty young age, I felt like if I never won a Grand Slam, then I wouldn't have lived up to what people thought I should have been,” she said after she took the title. “That was a pretty heavy burden to kind of carry around.” And it’s clear that Keys lifted that burden off of her shoulders, finally playing with joy. She stays aggressive but moves with a kind of cheekiness, sticking her tongue out when she hits a particularly tricky shot.

Keys suggests that you can want something too much. There’s a difference, perhaps, between wanting something so badly that you turn desire into pressure, versus recognizing your desire and letting it push you somewhere, collaboratively.

In the post-match interview I link above, Andreeva credits her mental game for her historic win. “It’s easy to be confident and it’s easy to play good when everything goes your way, when you feel like the ball is flying,” she says. “For me, the hardest part is to still be positive and to force yourself to be 100 percent mentally when something doesn’t go your way.“ I saw this while scrolling Twitter in bed on Monday morning. I had been sobbing the night before, dejected. I got up.

When I fall for these Rise-and-Grind 💯 sports narratives, I feel a bit like an idiot, but a willing one. In Tony Tulathimutte’s Rejection, the characters are defined by their reactions to various rejections: His characters are incels, aggrieved ex-lovers, and radical fetishists. They commit acts of domestic terrorism, buy exotic and extreme pets, and make everyone in the college co-op uncomfy. They are rejected, but many of them also do the rejecting, “[alienating] themselves so thoroughly from the world that they shrink to nothing,” as my friend

recounts in his discussion of the book.But don’t be mistaken; this supposed mental fortitude — Is that what we should call it? Maybe tenacity? — is not necessarily virtuous. In his aforementioned essay on rejection/Rejection John writes of a recent breakup:

At the time, you thought that a person with character would get over it quickly, move on from this stupid thing in a normal amount of time. (At some point, you are in Napa retelling the whole story to a group of people you don’t know very well. Halfway through, hearing the facts leave your mouth, you pause before admitting: “From this point on, the situationship was mostly in my head.” Everyone laughs. You feel lucky your cheeks were already flushed from the wine.)

What aspect of character is measured by the speed of your return to the status quo? Self-sufficiency, independence, cool indifference? Perhaps your failure to move on is a revealed preference for other values; disinterest would be dishonest.

Rejection was a disturbing book to read partly because I felt bad for the rejectees, and because I could see myself in them. Yet Tulathimutte does not treat these characters with much compassion, turning almost all of them into charicaturistic monsters. Parts of the book are overly absurd, written almost mockingly. I felt tremendously sad (perhaps the point) — Sure they are sick and depraved, but why hold so much contempt for the subjects of your inquiry?

I walked away from Rejection a little worried, admittedly, that I was too similar to his characters. Deviant, outcast, incel-ish, self-pitying. I was sobbing4 because I got politely turned down by a guy I went on a first date with who I didn’t even respect very much. I was so annoyed. I didn’t even want him! So why didn’t he want me?

This is, of course, all enormously dishonest. I did want him, or at least I wanted him to like me. I wanted it badly, or else why would I even bother to try?

some things:

first and foremost i apologize for no newsletter this past month. no excuse except for: im busy living ‘la vida loca’

this is 100% genuine - though i have exceeded my Q1 goal of going on 1 date, i am literally open to being set up with anyone and i’m soooo serious. if you know anyone in DC or on the east coast or even in America who you think would be down to hang out casually or noncasually. lmk

ok no more some things. sorry. like i said i’m busy living la vida loca. hanging out with my friends, going out, going to the dentist.

LOL jk. I caught up on Severance s2 finally, which has been very good, though not as good as s1. I’ve also been watching The Bachelor which has been tremendously low energy, though I’ve been watching it with my friends :) which is FUN ! also White Lotus s3, which tbh so far is a bit of snooze to me.

i’m literally looking at my google cal to figure out what it is i’ve been doing. i went to the doctor ? my LDLs are NOT high btw. Something i’m really proud to share

i’ve been doing this thing most weekends where I spend a few hours at a coffeeshop reading a book and journaling. it is frankly a way for me to avoid having to be around my roommates (though they are nice. i just like being alone..) but every time i do it i feel like this meme

ok that’s all. love you! xoxo

PM

sorry for so much tennis talk these days. LOL

perhaps it’s important to point out that the sexiness of tennis is also amplified by other factors — the wealth, the outfits, the athletes. the juxtaposition of propriety with intense passion…

This is also the primary argument of The Inner Game of Tennis, which I wrote about in my last letter, and which I need to stop talking about :)

and btw if anyone sends me a text like ‘:((( im sorry pegahhhh’ i’m going to be annoyed lol. just being up front about it

I stan a tennis fan!

ah pegah! I loved this! Thank you for continuing to write, and no you are at the very least definitely not bad (at least to me :D) at writing!